SPACE for Gosforth submission to Department for Transport’s “Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy Safety Review”, 1 June 2018

The Government’s Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy, published in April 2017, set out an aim of making cycling and walking the natural choices for shorter journeys or as part of a longer journey. In support of that, the government is conducting a cycling and walking safety review and in March 2018 issued a call for evidence asking “for great ideas, for evidence of what works, for examples of good practice from other countries, for innovative technologies, for imaginative solutions, and for idealism tempered with a sense of the practical”. The government is expected to publish a summary of responses, including the next steps, later in 2018.

SPACE for Gosforth submitted the following evidence to the review:

- Space for Gosforth (SPACE) is a group to promote and campaign for a Safe Pedestrian And Cycling Environment for Gosforth in Newcastle upon Tyne. We are residents of Gosforth, most of us with families and we walk, cycle, use public transport and drive. We are not affiliated to any other campaign group or political party.

- The aim of the organisation is to promote healthy, liveable, accessible and safe neighbourhoods where

- Walking and cycling are safe, practical and attractive travel options for residents of all ages and abilities.

- Streets are easier and safer to navigate for residents or visitors with limited mobility and for residents or visitors with disabilities or conditions for whom travel is a challenge.

- There is good walking and cycling access to local community destinations including schools, shops, medical centres, work-places and transport hubs.

- Streets are valued as places where people live, meet and socialise, and not just for travelling through.

- The negative consequences of excessive vehicle traffic including injury and illness from road traffic collisions, air pollution, community severance, noise pollution and delays are minimised.

- The public health benefits of healthy streets and active travel (walking and cycling) are compelling

- Air pollution: The Draft UK Air Quality Plan for tackling nitrogen dioxidepublished on 5 May 2017 confirms that “road transport is responsible for some 80% of NOx concentrations at roadside, with diesel vehicles the largest source in these local areas of greatest concern“. Poor air quality is responsible for 40,000 early deaths each year[1]. [Royal College of Physicians]. Some of the health risks of pollution include: cancer[2], lung cancer and heart failure[3], reduced lung capacity[4] and cognitive delay[5] in children, and links to dementia[6], infertility[7] and sperm damage[8].

- Cancer and heart disease: On 20 April 2017 the BBC reported[9]on a study[10] of 250,000 people over 5 years showing how much cancer and heart disease figures could be reduced by if people walked or cycled to work. This found that “regular cycling cut the risk of death from any cause by 41%, the incidence of cancer by 45% and heart disease by 46%.“, while walking to work reduced the risk of death from heart disease by 36%.

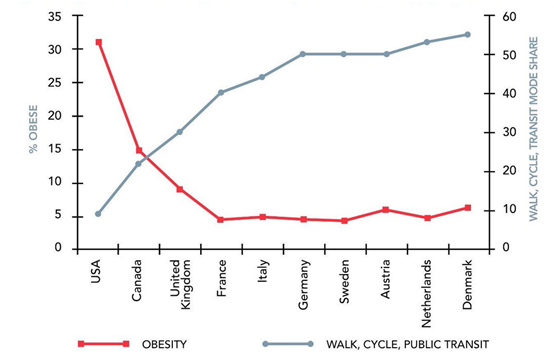

- A study of obesityin Europe and North America showed that “Countries with the highest levels of active transportation generally had the lowest obesity rates.”[11] Obesity is estimated to be responsible for 30,000 early deaths each year [12] [Public Health England].

Population-level relationship between obesity and combined walking, cycling and transit mode share[13]

- Inactivityhas been shown to be responsible for many more early deaths than obesity[14]. According to the British Heart Foundation Physical Activity Report 2017[15] 42% of adults in the North East are classed as being inactive.

- It is estimated that one in six deaths every year are directly due to inactivity[16]. This is about 84,500 in England and Wales. Sedentary lifestyles: are also linked to increased pressure on (and costs of) social care[17].

- Walking or cycling to work can also cut the chances of developing diabetesby 40-50% [18] as well as reducing the prevalence of dementia[19].

- Walking and cycling also have a proven positive benefit to mental health. A study of 18,000 adults[20]found that “Those who had an active commute were found to have a higher level of well-being than those who went by car or public transport. When researchers analysed the wellbeing of a small group who swapped the car or bus for a bike or going on foot, they found they became happier after the switch.”

- A separate study of 20,000 children[21]found that “Children who walk or cycle to school rather than being driven by their parents have an increased power of concentration, and the effect of this ‘exercise’ lasts all morning.”

- We welcome this call for evidence as increasing the number of people walking and cycling while reducing the risks to their safey is a moral, economic and public health imperative.

- We feel that road safety affects the personal decisions that we make for ourselves and our children. We regularly experience dangerous situations and even though we want to walk or cycle more, we feel forced to to limit our children’s independence and to use cars for some journeys because the roads don’t feel safe.

- In the run-up to the May 2018 local elections, we were keen to find out what the candidates thought, in particular about how they planned to address transport-related issues in our community. To do that we came up with five pledges and asked each of the candidates whether they supported these or, if not, what they planned to do instead. The five pledges we asked candidates to support were:

- Streets that are safe (and feel safe) for children to walk and cycle to school, to the shops or to the park.

- Air pollution in Newcastle brought within legal limits as soon as possible.

- Residential streets that are pleasant, safe and attractive places to live and where children can play out.

- Rapid implementation of temporary changes to trial interventions to support these objectives.

- Constructive community engagement about how to address the public health impacts of travel and the benefits of active travel.

- We recommend that there should be clear objectives that local authorities are expected to meet. These should include reducing the number of near misses and the number of injuries to and deaths of vulnerable road users (i.e. people walking or cycling), and creating an environment that feels safe enough that people who currently consider active travel (walking or cycling) too risky will feel that this is a safe and attractive option for them evidenced by a rise in the number of people cycling and walking, including the number of children walking or cycling to school.

- We welcome the range of questions asked as a multi-track approach is needed to achieve this, including improvements in infrastructure, public attitudes towards people walking and cycling, driver education, the law, and law enforcement. This approach should deliver safe space for cycling through a combination of more cycle paths which are separate from or physically protected from motorised traffic, lower speed limits where cyclists mix with other traffic or there are a large number of pedestrians, and better driver education and stronger law enforcement to protect pedestrians and cyclists from other traffic.

- We recommend that the government establishes a standing expert advisory group to advise government on the safety of vulnerable road users, to set targets for improvement and to monitor progress.

- In our response the six questions in this call for evidence, we use local examples to illustrate the risks that vulnerable road users face and how their safety can be improved. Against each question we provide relevant evidence and recommendations.

Question 1: Do you have any suggestions on the way in which the current approach to development and maintenance of road signs and infrastructure impacts the safety of cyclists and other vulnerable road users? How could it be improved?

- Poor infrastructure for walking and cycling is specific barrier that needs to be addressed, in particular to provide safe and direct routes for people walking and cycling. Providing cycle routes separated from other traffic will make cycling safer for people who already cycle and enable people who do not currently cycle to feel confident enough to start cycling.

- We would like to see greater weight attached to designing and redesigning residential streets so that the motorised traffic is largely residential ie the through traffic is reduced. In conjunction with a 20mph speed limit, these measures will make walking and cycling safer and more attractive options and so increase the number of people who choose to walk or cycle. Through traffic can be prevented by ‘modal filtering’, which prevents through motorised traffic while still allowing people to walk and cycle through, as shown in Fig 1. Simple and temporary measures, such as planters, can be used to trial modal filtering so that the placement of the filter can be trialled to find the best location before making the change permanent.

- There is good evidence that a 20mph speed limit in built up areas reduces vehicle emissions[22] and that reducing the speed limit from 30mph to 20mph reduces the number of casualties by 20%[23]. There is evidence from London[24] that the chances of being injured are 21% lower on 20mph streets compared to a 30mph streets. Calderdale[25] achieved a 30% reduction over 3 years by implementing 20mph speed limit across a wide area. We recommend that that a 20mph limit is introduced in all built up areas and enforced.

- The national British Social Attitudes Survey 2013 [26] identified a significant potential to increase the number of journeys being cycled instead of driven, but that the fear of traffic is a major barrier to people taking up cycling.

- When asked about the journeys of less than two miles that they now travelled by car

- 33% said that they could just as easily catch the bus

- 37% said they could just as easily cycle (if they had a bike)

- 40% of people agreed that they could just as easily walk.

- 61% of all respondents felt it is too dangerous for them to cycle on the roads, rising to 69% for women and 76% for those aged 65 and over.

- Research in our home city of Newcastle upon Tyne in 2015 tells a similar story [27]: 54% of people in the city said they could begin to ride a bike or ride their bike more often. When non-cyclists were asked about what kind of bike routes would help them to start cycling, 90% said traffic-free routes and 85% said bike lanes protected by a kerb.

- This evidence shows that the lack of quality of cycling infrastructure, in particular routes that are convenient and feel safe for cycling, is a key barrier to people taking up cycling. This should be addressed by a significant increase in annual investment on cycling infrastructure to overcome this barrier to cycling. This should be ongoing and at a level equivalent to that which has delivered quality infrastructure and high rates of cycling in other climatically similar[28] northern European countries such as Denmark (19% of trips are cycled) and the Netherlands (27%): these countries spend £24/person per year[29].

- In comparison, the government’s Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy commits to investing £1.2bn over 5 years, equivalent to £3 per person per year for walking and cycling together. However, there is widespread public support for a significant increase in public expenditure on cycling infrastructure to levels that match those in the Netherlands and Denmark; a survey[30] showed that 75% support more investment in cycling, with £26/person per year the average amount people want governments to be investing. Newcastle’s twin town of Groningen invests 85 Euros per person per year in cycling alone.

- The Department for Transport’s assessment[31] of a sample of cycle schemes found a benefit cost ratio (BCR) of 5.5:1 i.e. for every £1 of public money spent, the schemes provide £5.50 worth of benefit, meaning these “deliver very high value for money”. In comparison, the BCR for HS2 is between 1.4:1 and 2.5:1 [32]. We are therefore confident that investment in quality cycling infrastructure will be a very good investment of public money in itself, as well as a way of achieving safety improvements, increased levels of cycling and reductions in noise and air pollution. Given the significant health benefits of active travel (see para 3), Department for Transport’s economic appraisal methodologyshould take more account of public health in urban areas and place less weight on saving small amounts of time on journeys that are already short.

- To ensure that this investment delivers the quality of infrastructure that will provide people with a safe, easy to use and comfortable cycling experience, we recommend that local authorities do not ‘re-invent’ the wheel on how to deliver safe and attractive cycle infrastructure. The government can achieve this by mandating the adoption of approaches that have proved successful elsewhere in terms of high levels of cycling and low levels of injury, in particular the Dutch ‘Sustainable Safety’ approach[33] which seeks to prevent severe crashes and to (almost) eliminate severe injuries when crashes do occur, and which takes an integrated approach considering the ‘human’ (behavior), the ‘vehicle’ (including bicycles) and ‘road’ (design) and is based on five principles:

- Functionality (of roads)

- Homogeneity (of mass, speed and direction of road users)

- Predictability (of road course and road user behaviour by a recognizable road design)

- Forgivingness (of both the road/street environment and the road users)

- State awareness (by the road user)

- Alongside this Sustainable Safety approach, we recommend adoption of best practice in design and construction of cycling infrastructure, for example as documented in the London Cycling Design Standards 2014 [34].This documents six core outcomes which ‘together describe what good design for cycling should achieve: Safety, Directness, Comfort, Coherence, Attractiveness and Adaptability. These are based on international best practice and on an emerging consensus in London about aspects of that practice that we should adopt in the UK.

- Adopting the “Sustainable Safety” approach and Design Standards would prevent the variability that we have seen locally in even in newly built cycling infrastructure, with quality varying from the excellent to the downright dangerous.

- For example here is a new fully separated two way cyclepath in Newcastle city centre (Fig 2, left) and another new cycle lane in nearby Morpeth (Fig 3, right). The latter fails the 2nd of the Sustainable Safety principles of homogeneity as the it mixes cycles with faster and heavier vehicles. It also fails the 4th principle as the design is unforgiving of mistakes – if the lorry driver drifts into the cycle lane, the consequences for a person cycling could be serious injury or death

- The two pictures below show an advisory cycle lane on a busy road with a speed limit of 40mph. Fig 4 shows how vehicles enter the unprotected cycle lane with the result that people do not feel safe using the cycle lane and, as seen in Fig 5, choose to cycle on the pavement instead. This illustrates the importance of building cycle infrastructure to a high standard. Poor infrastructure that leaves cyclists unprotected will not be used by people who currently cycle and will do nothing to make people who currently do not cycle feel that it is safe for them to do so.

- This scheme fails the 2nd Sustainable Safety principle of homogeneity as it has fast and heavy motorised vehicles in close proximity to cycles which are slower and lighter vehicles. It also fails the 4th principle of forgivingness as the design is unforgiving of mistakes – if the bus driver drifts into the cycle lane, the consequences for a person cycling could be serious injury or death.

Fig 4

Fig 5

- There is a lack of consistency in other new facilities. Fig 6 (left) shows is a dedicated off road two way cycle path which feels safe enough to be used by young children and less confident or more risk averse adult cyclists. Fig 7 (right) shows a cycle line on a busy dual carriageway with light segregation from vehicular motorised traffic which would not be used by these groups.

- High quality cycling infrastructure also benefits people with disabilities who wish to cycle. For some people with disabilities, cycling is easier than walking and adapted or non-standard cycles are available for people who need them. Designing continuous cycle routes to a consistently high standard will mean that they are suitable for non-standard cycles and for people who cannot get off and walk. We also support the campaign by Wheels for Wellbeing[35] for 5% of all cycle parking spaces to be allocated for use by disabled cyclists since most cycle parking cannot accommodate non-standard cycles which can be wider than regular bicycles.

- In designing new infrastructure for people walking and cycling, shared space should be avoided as it creates conflict between these two different modes of transport and creates a risk of injury. With pedestrians and cyclists travelling at different speeds, shared space breaches the 2nd sustainable safety principles of homogeneity. It is also unsafe for people with visual impairments as they may be unaware of approaching bicycles and fear of injury may mean that their movements are restricted.

- The RNIB has an ‘accessible streets’ campaign to make the streets more accessible to people with visual impairments. This covers a range of issues including tactile paving, pedestrian crossings and obstacles such as pavement parking and street clutter. Newcastle City Council has backed this campaign and we look forward to seeing the benefits of this locally in future. We recommend that all local authorities should back this campaign.

- With the rollout of EV charging infrastructure, it is important that on-street chargers are placed where they do not obstruct pavements or cycle paths. We have provided detailed evidence on this to the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee inquiry “Electric vehicles: developing the market and infrastructure”. The key points are

- Equalities policy means streets must be accessible to those with disabilities, who use wheelchairs or otherwise less mobile. For these reasons, recharging equipment should be placed so that it does not impinge upon safe and convenient movement of pedestrians on the pavement, should avoid placement on the pavement and avoid any trip hazards due to trailing cables when in use. Ideally charging equipment should be placed in the carriageway, not on the pavement.

- Well designed and well positioned charging infrastructure offers opportunities to improve the urban realm:

- by providing additional facilities that benefit all users eg the charging station could include features such as seating, charging for electric bikes, street maps, other displays of local information, wifi etc.

- By consolidation other street features / facilities onto the charging station to minimize pavement clutter eg telephones, or parking restriction notices displayed at the charging station rather than on a separate post on the pavement.

- We recommend that policy and guidance is developed to address these issues and that regulations relating to EV charging points should include guidance for placement so that they are consistent with other government guidance. This will help to ensure that the take-up of EVs does not disadvantage pedestrians and gives full consideration to pedestrians with additional needs eg wheelchair users, people with buggies, visually impaired. As electric charging points proliferate, it is vital that policy and guidance is quickly developed and disseminated to avoid making things worse for active travel and for vulnerable road users.

- We present below a selection of photographs that show charging infrastructure being provided in ways which disadvantage people walking (Fig 8), and charging infrastructure being provided in the carriageway which does not adversely affect people walking (Fig 9) and which also accommodates cycle parking (Fig 10). This last image also provides an example of how the same charging point could be used to charge electric cars and electric bikes if the design is appropriate.

Fig 8: The slalom and narrowing of the available pavement makes this particularly problematic for people walking, especially those with wheelchairs or buggies (photo @k9)

Fig 9: placement in the carriageway (photo @mum_on_bike)

Fig 10: EV charging point with integrated cycle parking (Photo @PereSoriaAlcaza)

- We often see drivers endangering other road users, with particular risk to people walking or cycling, by driving through traffic lights and pedestrian crossings when they are on red, and/or while using a mobile phone. This is particularly concerning as we often see it at crossings that are busy with school children and people using our local high street.. When these incidents are reported to the police we have found an unwillingness to take any action at all without video evidence. We recommend wider use of cameras at such locations to provide the evidence that will enable the police to take action to protect vulnerable road users.

- We recognise that our recommendations represent a significant change for the traffic engineers in local authorities so we recommend that adequate training is provided to enable them to learn about these new approaches and so that they are able to deliver schemes to the standards required.

- We also recognise that making road changes to improve walking and cycling can be expensive and that it is important to get them right. It can be useful to trial road changes, and adjust them, before making them permanent. Newcastle City Council has recently trialled road changes and we recommend that this approach should be used more widely.

Recommendations:

- Residential streets to be redesigned to remove through traffic

- Implement 20mph speed limits in all built up areas

- Ongoing investment in infrastructure for safe walking and cycling at levels equivalent to the Netherlands

- Department for Transport’s economic appraisal methodology should take more account of public health in urban areas and place less weight on saving small amounts of time.

- Adopt the ‘Sustainable Safety’ approach used in the Netherlands

- Adopt best practice in design and construction of cycling infrastructure, for example as documented in the London Cycling Design Standards 2014

- Cycle infrastructure to be designed to be fully inclusive and 5% of cycle parking to be allocated to disabled cyclists.

- Avoid creating shared space for pedestrians and cyclists.

- Local authorities to back the RNIB’s accessible streets campaign

- Policy and guidance should be developed to prevent EV charging points impeding or inconveniencing people walking and cycling. Regulations relating to EV charging points should include guidance for their placement so that the regulations are consistent with other government guidance such as the Equalities Act.

- Wider use of cameras at traffic lights and pedestrian crossings to provide the evidence that will enable the police to take action against dangerous drivers.

- Training for traffic engineers to enable them to deliver schemes to the standards required

- Trial road changes before making them permanent

Question 2: Please set out any areas where you consider the laws or rules relating to road safety and their enforcement, with particular reference to cyclists and pedestrians, could be used to support the Government’s aim of improving cycling and walking safety whilst promoting more active travel.

Changes in the law

- Parking on pavements damages pavements creating a trip hazard for pedestrians. People can be forced to walk in the road to get past the parked vehicle which is awkward and dangerous especially for people using a wheelchair or child’s buggy or with a visual impairment. Pavement parking is illegal in London and this should be extended to the rest of the UK so that all pedestrians are protected from the dangers of pavement parking. We support the proposal from Living Streets that there should be a default ban, with pavement parking only allowed in certain circumstances on streets that have been specially designated to allow it, making it the exception rather than the rule.

Law enforcement

- Enforcing the laws that are in place and with stronger sentencing would go a long way towards dealing with dangerous driving and so improving cycling and walking safety.

- The well known West Midlands Police Close Pass Operation[36] is a good example of education and enforcement combined. Northumbria police conducted a similar operation in 2017 but only for one month [37]. We recommend that all police forces should be encouraged to copy the West Midlands Police scheme and to repeat it at regular intervals.

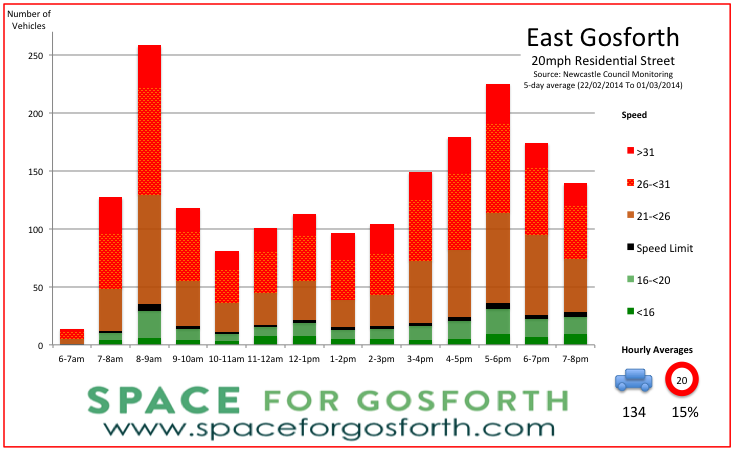

- While Newcastle has a large number of residential areas with 20mph limit, this is not enforced with the consequence that the speed limit is regularly flouted, putting vulnerable road users at risk. The chart in Fig 11 shows the number of drivers exceeding the speed limit on a 20mph residential street in Gosforth. Overall more than 85% of drivers break the speed limit, and over 200 drivers an hour broke the speed limit on that street between 8am and 9am, a time when children are making their way to school.

Fig 11

- We recommend enforcement of all speed limits, particularly in 20mph and 30mph roads where there are more likely to be higher numbers of vulnerable road users.

- We have observed very variable responses from the police in incidents that our members have reported, and in some cases this does not support vulnerable road users. In a recent case, a local resident was cycling along a main road in daylight. A car pulled out of a side-road and knocked her off her bike. The police questioned her about the colour of her clothing, and whether she was wearing hi-vis and using lights (even though it was light). This is inappropriate because she was travelling in accordance with the highway code whereas the driver had clearly breached the highway code as he had failed to yield to traffic that had priority by virtue of being on the main road. However, she was being treated by the police as if she, rather than the driver, was responsible for the collision. The police have successfully taken steps to improve the way other types of crime are handled, focussing on the actions of the offender rather than the victim’s clothing or behaviour, and a similar approach could also deliver improvements here too.

- Our members have reported dangerous close passes by drivers overtaking them while they were cycling, or drivers going through traffic lights and pedestrian crossings on red. In some cases the police have taken a statement and been to speak to the driver concerned and the incident recorded against the driver. In others, the police have said that it’s just one person’s word against another so they wouldn’t do anything, not even take a statement and record the incident. We recommend that every police force should contact drivers reported for dangerous driving that endangers people walking or cycling and should provide good quality educational material that explains the standard of driving required, and this procedure should be followed regardless of whether there is any other supporting evidence.

- We are very concerned that dangerous driving is being treated with leniency in the court system meaning that there is no effective deterrent. In another local example, a professional driver was caught by Northumbria Police with his mobile phone while driving. Given the recent changes to the legislation, we would have expected that this would have resulted in at least a driving ban, especially as he already had 10 points on his licence for three speeding offences. However the magistrate accepted his excuses that he was merely picking glass off the screen, that he was usually a competent driver and that he would suffer hardship as he would lose his job and consequently his house. He received a fine of only £190 plus costs, and a ban was waived as would cause him “exceptional hardship” [38]There is a long line of legal cases showing that this type of judgement does not deter drivers who use their mobile phones, and that some will continue to use them until they kill or seriously hurt someone. Gosforth is a suburb busy with traffic, and it is not unusual to see drivers using their mobiles while driving, or sitting with their engine idling (which is also illegal).

- This type of behaviour must stop because it is unacceptable and puts lives at risk. There needs to be a realistic chance of prosecution especially where one road user puts others in danger. Losing a license and having to retake the driving test would be a much more effective deterrent than a fine. If Magistrates are not giving sentences that form an adequate deterrent then we suggest that the law that revokes the licences of new drivers (with 6 points within the first 2 years) is extended to all drivers, or at the very least to professional drivers, who should be setting the standard. The excuse that losing a licence would create hardship is very unsatisfactory, as if other professionals committed similar offences that endangered others in the course of their employment they would expect disciplinary action at the very least and probably dismissal.

Recommendations:

- A national ban on pavement parking with pavement parking only allowed in certain circumstances on streets that have been specially designated to allow it

- Successful initiatives such as the West Midlands Police close pass operation to be rolled out nation-wide.

- Stronger enforcement of speed limits, particularly in 20mph and 30mph areas where there are likely to be larger numbers of vulnerable road users.

- Training for police on how to handle incidents involving vulnerable road users, particularly cyclists where the police response can be inappropriate.

- Police to contact drivers reported for dangerous driving with good quality educational material that explains the standard of driving required, regardless of whether there is any other supporting evidence.

- Stronger sentencing for people convicted of dangerous driving with more use of sentences that revoke the driving licence.

Question 3: Do you have any suggestions for improving the way road users are trained, with specific consideration to protecting cyclists and pedestrians?

- We think training drivers about vulnerable road users can be improved.

- There are driver training companies whose curriculum could include more on this eg the recent “Young Driver”[39] event held in Newcastle and sponsored by Vauxhall. These companies could be encouraged to teach young people and children beginning their driving career about how to drive in a way that reduces risk to vulnerable road users.

- The Pass Plus scheme[40] is supported by many local authorities by offering discounts and is a good opportunity to emphasise the needs of vulnerable road users but appears to have little in its current content.

- Training on how drivers can protect vulnerable road users could be given more emphasis by driving schools and instructors and in the Pass Plus lessons. An example lesson plan[41] from the on-line resource for learner drivers is very weak on drivers meeting other traffic particularly cyclists, saying to take care passing cyclists but only if they are a child or it is windy. In contrast there is much better training material available such as the excellent video[42] from Chris Boardman which shows the issues far better.

- It is clear to us that driver training across all areas can be greatly improved with respect to people cycling and walking. Driving schools registration and inspection systems can be made to address this by government and LAs.

- To emphasise their responsibility to more vulnerable road users, we recommend making it compulsory for all new drivers (and people retaking the test) to undertake awareness training as part of their initial test. This would combine the existing speed awareness training and the new awareness course about vulnerable road users described in our response to question 4, para 48-49).

Recommendations:

- Comprehensive coverage of the needs of vulnerable road users should be included at all levels of driver training including Young Drivers (under 17), driving schools and the Pass Plus training.

- This should be encouraged and promoted by the driving schools inspection and registration system.

- Insurance companies should accept certification of completion of this training as evidence of competence and discounts offered.

- Vulnerable road user awareness training to be a compulsory part of passing the driving test.

Question 4: Do you have any suggestions on how we can improve road user education to help support more and safer walking and cycling?

Education for all drivers

- The government has contact every year with every vehicle owner through licensing and MOTs plus of course less regular touchpoints through driver licensing and vehicle registration. There is an opportunity to deliver safety messages at these times, directly reaching all drivers at low cost. For example, for correspondence delivered by post, messages/images could be printed on the outside of envelope or inserted as an additional leaflet. For people carrying out an online transaction, they could be required to watch a short video before proceeding to complete their transaction. These safety messages should be developed in conjuction with and approved by organisations representing vulnerable road users such as British Cycling and Living Streets.

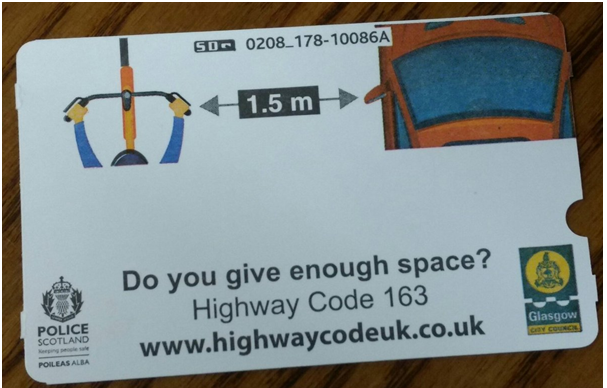

- The image in Fig 12 below is on the reverse of a car parking ticket. This is a good example of how an important message can be presented powerfully and simply, direct to the intended audience. This is a good example of an image that could be printed on the outside of envelopes sent by DVLA.

Fig 12

Education for drivers after an incident involving a vulnerable road user

- Speed Awareness courses have been shown to be an effective alternative to prosecution. There is evidence they change attitudes and driving behaviour. See the “Evaluation of the National Speed Awareness Course”[43] report commissioned by the Association of Chief Police Officers for England, Wales and Northern Ireland National Driver Offender Retraining Scheme and the Association of National Driver Improvement Service Providers.

- We would like to see this effective approach extended with a similar awareness course focusing on safe driving around people walking and cycling as an alternative to prosecution for drivers who commit traffic offences involving these vulnerable road users. This would cover a range of topics including how to safely overtake people cycling.

Education for professional drivers

- We have observed that it is disproportionately professional drivers who pass cyclists too closely when overtaking or who drive through red lights putting all other road users, especially vulnerable road users at risk. In a tragic local case, a young man Daniel Rushton who was crossing a road was killed by a taxi driver who went through a red light[44].

- Whatever an individual driver’s standard of driving, the more they drive, the greater the chance that they will be responsible for a collision. As professional drivers are generally high-mileage drivers, this makes the risks that such behaviour presents even higher. As a result we recommend that all professional drivers should be required to undertake some form of education, repeated at regular intervals, say every 5 years, as a condition of retaining their ability to drive professionally.

Recommendations:

- Department for Transport and DVLA to Include safety messaging in its interactions with drivers both in written correspondence and online, the safety messages to be developed in conjuction with and approved by organisations representing vulnerable road users such as British Cycling and Living Streets.

- Develop and implement a new ‘vulnerable road users awareness course’ to be taken by all prior to passing their driving test and (where appropriate) offered to offending drivers as an alternative to prosecution.

- All professional drivers to undertake some form of education, repeated at regular intervals, say every 5 years as a condition of retaining their ability to drive professionally.

Question 5: Do you have any suggestions on how Government policy on vehicles and equipment could improve safety of cyclists and pedestrians, whilst continuing to promote more walking and cycling?

- Speed is a significant factor in collisions and affects the chances of vulnerable road users surviving the impact. Speed limits exist to protect all road users but are regularly flouted. GPS-based speed limiting devices could bring about a significant reduction in speeding and risk to vulnerable users. We would like this to become a legal requirement in new vehicles. In the meantime, we would like to see insurance companies offering a discount to drivers with vehicles fitted with these devices.

- HGVs are involved in a disproportionate number of deaths of vulnerable users, with HGV blind spots being a major contributory factor in fatal collisions involving cyclists and pedestrians. To address this the mayor of London has introduced the Direct Vision Standard for HGVs[45] which rates all HGVs on a scale of 0 (lowest) to 5 (highest), based on how much a HGV driver can see directly through their cab windows, as opposed to indirectly through cameras or mirrors. Under the HGV Safety Standard Permit (HSSP) Scheme, it is intended that from 2020 all HGVs over 12 tonnes will have to hold a safety permit when entering or operating in London. From 2020, HGVs rated 1-star and above would automatically be granted a permit, while those rated 0-star (lowest) would have to meet a safe system. By 2024 only HGVs rated 3-star and above, or those with an advanced safe system, would be allowed on London’s streets. This approach should be adopted on a national basis.

- Some people advocate measures such as compulsory helmets and hi-vis, believing that these would make cycling safer. However, helmets have been shown to make little difference to overall cycling safety[46], [47], and studies show that high-vis clothing has little or no effect on cycling safety, or on the behaviour of people driving[48] [49]. However, making such equipment mandatory does reduce the numbers of people cycling[50], with a loss of the public health benefit from the activity. We therefore recommend that safety equipment for cyclists should be mandated only where there is a clear overall public health benefit that takes into account the benefits of physical activity.

- Some people advocate registration and licensing of cyclists. Driver registration and vehicle licensing are appropriate because motorised vehicles present a substantial risk to people or property. Cycling does not present a substantial risk, so registration and licensing are not appropriate and would simply present a barrier to cycling, contrary to the objective of the CWIS, or criminalise large numbers of people without any real benefit. We therefore recommend that there should be no requirement for registration or licensing of cyclists or cycles

Recommendations:

- GPS-based speed limiting devices to become a legal requirement in new vehicles in future, with an interim step of insurance companies offering a discount to drivers with vehicles fitted with these devices

- Nationwide adoption of London’s HGV Direct Vision Standard and HGV Safety Standard Permit scheme.

- Only mandate safety equipment for cyclists where there is a clear overall public health benefit that takes into account the benefits of physical activity.

- No registration or licensing of cyclists or cycles

Question 6: What can Government do to support better understanding and awareness of different types of road user in relation to cycle use in particular?

- The suggestions made about education for all drivers (in response to question 4, para 46 & 47) can help drivers better understand the experience of people cycling and how drivers should behave around them

- We are concerned about attitudes towards cycling and people who cycle that endanger people who do cycle and put off people from taking it up. Our members have experienced verbal abuse and threatening and intimidating behaviour while cycling, for example shouting and swearing (eg “get out of the f***ing road”), revving the engine while closely following a person cycling, and deliberate close passes when overtaking. On social media we observe people who cycle as being portrayed as some ‘other’ group and hostility towards them through comments such as “knock them all off” and “they should get off the road because they don’t pay for them” (which is irrelevant as roads are funded from general taxation).

- If we are to increase the number of people cycling these attitudes need to be challenged and changed. This is entirely possible as attitudes have changed on other issues such as racial discrimination and drink driving.

- There is research on understanding heuristic and systematised cognitive processes to help identify ‘nudges’ that might work[51] and these principles could be used in sophisticated road safety campaigns.

- Other examples of actions which have potential to change attitudes are giving drivers experience of what cycling on a busy road is like seen in this YouTube video of bus drivers in Mexico[52] or encouraging internalisation by using the ‘Place loved one here’ captioned photographs (Fig 13).

Fig 13

- There is also a view that cyclists are the cause of congestion which does not stand up to scrunity[53]. It is important to counter this view by raising people’s awareness of the benefits of cycling in terms of being a space-efficient way of moving people in urban areas as well as having wider individual and public health benefits.

Recommendations:

- The government should set up a small permanent multidisciplinary committee including psychologists, educationalists, communication specialists, politicians and civil servants, cycling, motoring and pedestrian group representatives to bring together the evidence and plan interventions to begin to change attitudes to active travel, particularly of drivers towards vulnerable road users. This committed should report to the expert advisory group recommended in para 9.

[1] https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/every-breath-we-take-lifelong-impact-air-pollution

[2] http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/causes-of-cancer/air-pollution-radon-gas-and-cancer/how-air-pollution-can-cause-cancer

[3] https://www.nhs.uk/news/cancer/air-pollution-linked-to-lung-cancer-and-heart-failure/

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/may/19/why-air-pollution-in-schools-is-such-a-big-deal-and-what-to-do-about-it

[5] http://www.newsweek.com/children-exposed-air-pollution-school-may-be-cognitively-delayed-study-finds-311099

[6] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/news/6386775/Air-pollution-linked-to-early-form-of-dementia.html

[7] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-fertility-airpollution-idUSKCN0UT2MF

[8] https://www.theguardian.com/waste/story/0,12188,1579161,00.html

[9] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-39641122

[10] https://www.bmj.com/content/357/bmj.j1456

[11] http://www.humankinetics.com/acucustom/sitename/Documents/DocumentItem/15891.pdf

[12] http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160805122054tf_/https://www.noo.org.uk/NOO_about_obesity/mortality

[13] http://www.humankinetics.com/acucustom/sitename/Documents/DocumentItem/15891.pdf

[14] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-30812439

[15] https://www.bhf.org.uk/publications/statistics/physical-inactivity-report-2017

[16] http://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-2805691/One-six-deaths-lack-exercise-Britain-worst-West-inactivity.html

[17] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/dec/15/sedentary-lifestyles-social-care-crisis-exercise-ill-health-old-age

[18] https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2013-08/icl-wtw080513.php

[19] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)60766-1/fulltext

[20] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-29175088

[21] http://sciencenordic.com/children-who-walk-school-concentrate-better

[22] http://www.20splenty.org/emission_reductions

[23] http://www.20splenty.org/20mph_casualty_reduction

[24] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0001457518301076

[25] http://www.20splenty.org/calderdale20success

[26] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/british-social-attitudes-survey-2013

[27] http://www.sustrans.org.uk/sites/default/files/bike_life_newcastle_2015.pdf

[28] https://www.spaceforgosforth.com/drier_than_amsterdam/

[29] http://www.ciwem.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Cycling-and-walking-investment-strategy-PATTH-response.pdf

[30] http://www.sustrans.org.uk/bike-life/overall-survey

[31] https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/348943/vfm-assessment-of-cycling-grants.pdf

[32] https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/3651/hs2-economic-case-value-for-money.pdf

[33] https://bicycledutch.wordpress.com/2012/01/02/sustainable-safety/

[34] https://tfl.gov.uk/corporate/publications-and-reports/streets-toolkit#on-this-page-1

[35] https://wheelsforwellbeing.org.uk/campaigning/

[36] https://west-midlands.police.uk/news/3951/serious-cycle-smashes-down-fifth-close-pass-first-year

[37] https://www.northumbria.police.uk/news_and_events/latest_news/2017/03/07/new_campaign_to_protect_cyclists_on_the_road/

[38] https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/gavin-hetherington-mobile-phone-a1-14514209

[39] https://www.youngdriver.eu/venues/northern/Newcastle_Racecourse

[40] https://www.gov.uk/pass-plus/how-pass-plus-training-works

[41] http://www.learners-guide.co.uk/lessons/meeting-traffic/

[42] http://www.cyclingweekly.com/news/latest-news/watch-chris-boardman-explains-how-to-safely-overtake-cyclists-186697

[43] https://ndors.org.uk/files/6614/4983/2018/Final_Speed_Awareness_Evaluation_Report_v1.4.pdf

[44] https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/taxi-driver-who-killed-beautiful-12205328

[45] https://tfl.gov.uk/info-for/deliveries-in-london/delivering-safely/direct-vision-in-heavy-goods-vehicles#on-this-page-0

[46] https://cyclingfallacies.com/en/29/people-should-wear-helmets-when-cycling

[47] https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/article/20171126-Chris-Boardman-0

[48] https://www.bikebiz.com/news/hivis-compulsion-study

[49] https://cyclingfallacies.com/en/19/people-should-wear-hi-viz-when-cycling

[50] http://road.cc/content/news/160654-aussie-helmet-law-does-more-harm-good-senate-hears

[51] http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2002-02215-008

[52] https://youtu.be/4SgtlwTGAz8

[53] https://cyclingfallacies.com/en/12/cycling-causes-congestion