The Government has directed Newcastle City Council to meet air quality limits in the shortest possible timescales. To achieve that, the Council must use the most effective and fastest acting measures to reduce pollution in locations where legal limits are not being met.

Measures that take longer or are not as effective may also be included in the plan in addition, but not instead of, the most effective measures.

We thought we would take a look to see what the evidence says.

Broadly speaking, roadside air pollution can be reduced in one of three main ways.

- By reducing the number of polluting vehicles

- By reducing the amount of pollution emitted per vehicle

- By reducing people’s exposure to pollution

We’ll look at each of these in turn.

1. Reducing the number of polluting vehicles

Options that have been proposed to reduce the number of vehicles include:

- Banning certain vehicles, or all vehicles, from a specific location.

- Charging vehicles entering or passing a specific location, which could include road tolls or parking charges.

- Constraining the number of vehicles that can use a given route.

- Parking restrictions.

- Investing in alternative low/zero emission methods of transport such as public transport, walking or cycling to encourage people to leave their car at home.

- Reducing the need for travel through planning e.g. by locating shops and schools close to where people live.

- Information campaigns to persuade people to travel less or use less polluting forms of transport.

In the Technical Report accompanying the Government’s UK Air Quality Plan it states that charging the most polluting vehicles is one of the most effective ways to reduce pollution. A separate review by Public Health England showed that “driving restrictions produced the largest scale and most consistent reductions in air pollution levels, with the most robust studies.”

The London Congestion Charge has demonstrated that exemptions must be limited in scope to avoid exempt traffic expanding to fill the space. In London “Exempting buses and taxis meant that these diesel vehicles drove many more miles as a result of the congestion charge as commuters transferred out of personal cars into these forms of public transport. As a consequence, the fuel mix of vehicles in the zone moved toward diesel to such an extent that diesel miles increased.” Older buses and private hire vehicles are now being charged from April 2019 to rectify this.

The Council’s Air Quality Status report provides an assessment of the measures currently being used to address air quality in Newcastle. All but four of these are classed low (or imperceptible) impact. The remaining four are: increasing public transport priority, low emission zone, higher parking charges and electric vehicle charging infrastructure.

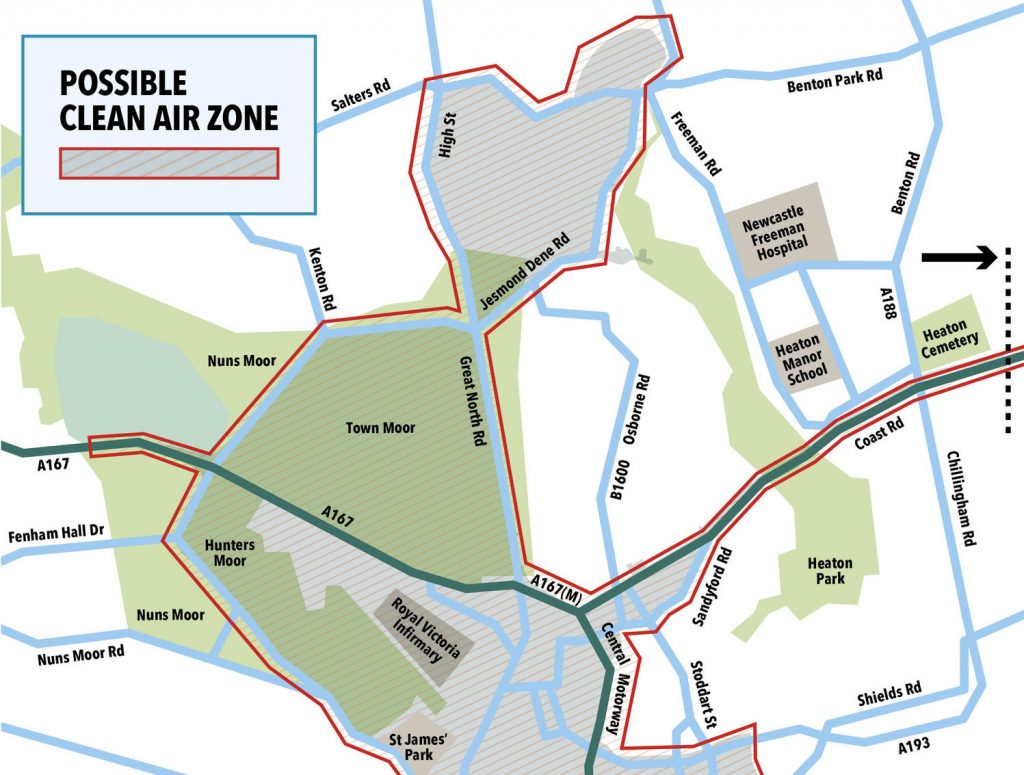

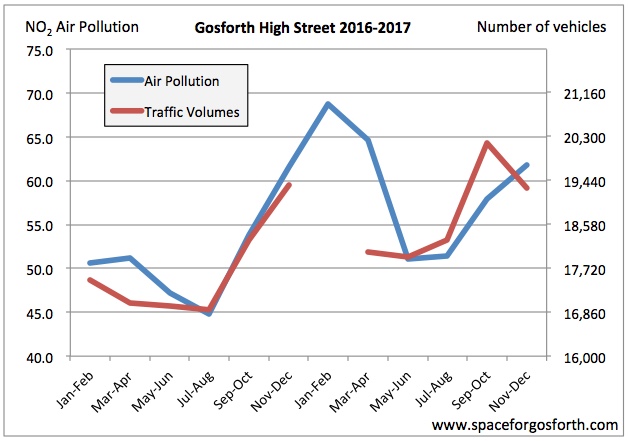

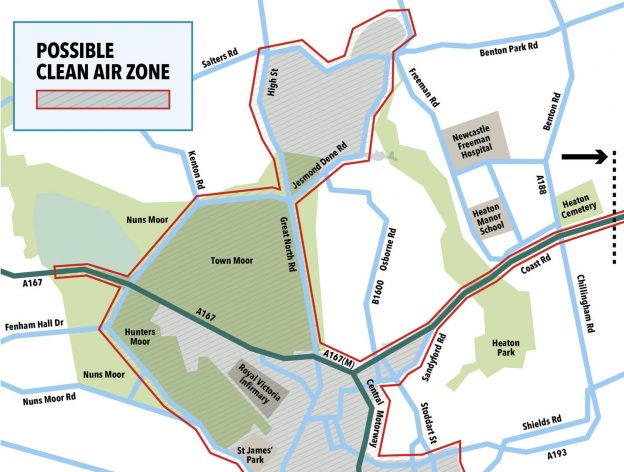

Of these increasing public transport priority, which we presume means bus (or no car) lanes makes buses more attractive and also reduces vehicle capacity. Our analysis of traffic levels on Gosforth High Street suggests that constraining vehicle throughput does improve air quality.

Parking charges, or bans, are likely to have a similar effect to road charging, but only affecting traffic to a destination rather than just passing through. For example, increasing parking charges in central Newcastle would reduce the number of vehicles driven into the city centre but would not impact any vehicles driving through the city. For that, road charging or access restrictions would be required.

Investing in walking and cycling creates more choice for how people travel and has many other benefits and probably the greatest benefit for public health, but is only likely to be effective in reducing air pollution if accompanied by restrictions on vehicle travel. For example, the cycle lanes on the Great North Road have been built without reducing the number of vehicles lanes so do not constrain vehicle use. Possibly some people will have given up their car for certain journeys in favour of cycling, but that could be offset e.g. if others divert to that route because it is quicker from having less traffic.

Likewise, an increase in bus services is unlikely to reduce the overall volumes of traffic, nor will making bus travel cheap or even free. That’s not to say there are not benefits to investing in good quality public transport, just that by itself it would not make much difference to air quality. The same is likely to be true for investments in park and ride.

Planning services to be near where people live is important and likely to be effective but only in the longer term.

Information campaigns are likely to be beneficial when accompanied by other measures but are likely to be ineffective if e.g. the objective is to persuade people to leave their car at home in favour of other modes that, as a result of long-term underinvestment, are slower, more expensive or involve greater personal risk.

2. Reducing the amount of pollution emitted per vehicle

Options that have been proposed to reduce the amount of pollution emitted per vehicle include:

- Setting standards for vehicle engine emissions.

- Retro-fitting buses, HGVs or taxis.

- Traffic management e.g. smart traffic lights or speed restrictions. Scrappage schemes.

- Anti-idling campaigns.

Vehicle emission standards have been effective over the long term in reducing emissions and improving air quality, although those improvements have recently stalled due to the Diesel-gate scandal where it was found that some car manufacturers were illegally cheating on emission tests. This is not a measure that can be targeted at specific locations, nor would it be effective in the short term.

In the Government’s Air Quality Plan Technical Report it shows there is a benefit to retro-fitting buses, HGVs and taxis but this is substantially less effective than a clean air zone (0.09μg/m3 for retro-fitting vs 8.6μg/m3 for clean air zones.) On Gosforth High Street we found that pollution did not improve after Arriva introduced newer buses although these were still not the most recent EURO VI standard.

The Government’s Air Quality Plan said about measures to optimise traffic flow that “there is considerable uncertainty on the real world impacts of such actions“. This is because rather than reducing air pollution, changes that are designed to improve or optimise flow can lead to more traffic (and more pollution).

Reducing speed limits can be effective. On major roads such as the A1 or A19, restricting speeds to 60mph or 50mph has been shown to improve air quality. On urban roads, there is evidence that lower speed limits e.g. 20mph can improve air quality by a small amount.

Targeted scrappage schemes have potential to improve air quality although the Government’s “analysis of previous schemes has shown poor value for the taxpayer and that they are open to a degree of fraud.”

There is limited evidence as to whether anti-idling campaigns are effective, although they could be beneficial in specific locations e.g. outside schools or hospitals where there are people who are more vulnerable to poor air quality.

3. Reducing people’s exposure to pollution

Options that have been proposed to reduce people’s exposure to pollution include:

- Encouraging people to avoid main roads.

- Vegetation such as trees or hedges.

Encouraging people who are walking or cycling to avoid main roads can reduce that individual’s exposure but does not help to reduce air pollution levels. There are often situations where main roads cannot be avoided, for example it the length of the detour would be prohibitive or if the main road itself is a destination such as Gosforth High Street.

This also does not help people in cars or taxis, especially professional drivers who are more at risk because pollution levels are higher inside vehicles.

Plants and trees do remove air pollution from the atmosphere but a large amount of vegetation is required to make any meaningful difference. For this reason plants and trees are not particularly useful for improving air quality in urban areas, although they do have many other benefits. Certainly there is no harm in additional vegetation as long as it does not prevent dispersal of air pollution.

It has been shown that dense hedges can reduce exposure by creating a barrier between people and the source of the pollution, including in street canyons such as Gosforth High Street. Trees in the same situation, on the other hand, could make pollution worse by preventing dispersion.

Summary

Overall it is clear that the most effective and fast acting ways to reduce air pollution are forms of road charging and / or driving restrictions (including parking charging/restrictions). Targeted retrofitting at the most polluting vehicles, most likely buses and HGVs, will also have a positive effect. Any plan or proposal to meet air quality limits in the shortest possible timescales is likely to need both of these elements.

The most effective plan will require a combination of measures adapted to the specific local situations. For example, a large proportion of air pollution in the centre of Newcastle will come from buses and taxis. On The Coast Road and Central Motorway much more pollution will be due to private vehicles.

Interventions to support and enable active travel and public transport can be proposed in addition (but not instead of) to the above measures to give people the best possible choice of alternative options for how to travel. For cycling the fastest uptakes have been achieved through the implementation of high quality safe cycling routes that work for all ages and abilities.

Other elements can also be included in the plan to help people adjust. To quote Public Health England “Some evidence-based actions may disproportionally affect some groups of people. For example, those whose livelihoods depend on driving but who do not have access to or the resources for cleaner vehicles may need particular support because some of the most effective interventions target road vehicle emissions. Without such support, action on air quality may have the perverse impact of increasing inequalities.“

Evidence Sources

The main sources for this blog are:

- The Government’s UK Air Quality Plan Technical Report

- The Government’s Clean Air Zone Framework

- Public Health England’s Review of interventions to improve outdoor air quality and public health

- National Audit Office report on Air Quality

- NICE Guideline [NG70] Air pollution: outdoor air quality and health

- EU Joint Research Centre Catalogue of Air Quality Measures

- Newcastle City Council’s Air Quality Annual Status Report 2018

Additional information and evidence from:

- Road pricing most effective in reducing vehicle emissions

- The Only Hope for Reducing Traffic

- London’s congestion charge has increased deadly diesel pollution by a fifth

- Can free public transport really reduce pollution?

- Does transit really reduce congestion?

- Plants and trees ‘not the solution’ to air pollution in cities

- Cities need to ‘green up’ to reduce impact of air pollution

- Disappearing traffic? The story so far

- Disappearing traffic?

- Do emissions and fuel used increase with 20mph limits?

- Diesel cars emit 10 times more toxic pollution than trucks and buses, data shows

- Diesels more polluting below 18C, research suggests

- No improvement in average efficiency of new cars for four years

- Does Free-Flowing Car Traffic Reduce Fuel Consumption and Air Pollution?

- Roadworks, Air Quality and Disappearing Traffic – SPACE for Gosforth

- Ignore the toxic myth about bike lanes and pollution – the facts utterly debunk it

- If you build them, they will come: record year for cycle counters

- What you need to know about the proposed bus ‘Quality Contract Scheme’

- Higher air pollution health risk inside car, study finds

If you are aware of any other evidence that might usefully be included in this blog please do let us know via the comments section below.

An idling vehicle produces almost twice the emissions as a moving vehicle. An engine restart is equivalent to less than 10 seconds idling (30 seconds at max for older vehicles). During rush hour on the busiest most congested roads, vehicles spend more time idling than moving. An vehicle accelerating from a stationary position produces 10 times the emissions as a moving vehicle. So when vehicles are in start-stop-idling traffic the vast majority of pollution could be avoided by effective traffic management to reduce start stop idling. One day we’ll say “If you insist on driving in rush hour, we’ll insist you do so in the least polluting way. Stop, switch off and wait till the section of road ahead is clear to drive on. We’ve closed the side roads (LTNs/school streets/clean air routes) so you’ll catch up with that same vehicle that’s ahead of you. You’ll have the same journey time but produce 70% less emissions. Less air pollution for you in the car and for everyone that’s breathing the toxic air coming out of your vehicle’s exhaust pipe.”

Parking fees effective in reducing congestion associated with parking

https://www.cdhowe.org/sites/default/files/attachments/research_papers/mixed//commentary_248.pdf

City Dwellers Don’t Like The Idea Of Congestion Pricing — But They Get Over It

https://www.npr.org/2019/05/07/720805841/city-dwellers-dont-like-the-idea-of-congestion-pricing-but-they-get-over-it

Urban Myth Busting: Congestion, Idling, and Carbon Emissions

https://usa.streetsblog.org/2017/07/06/urban-myth-busting-congestion-idling-and-carbon-emissions/

“Air pollution at roadside hotspots reduced dramatically after the Welsh Government began enforcing lower speed limits with cameras.” https://www.highwaycivilengineering.co.uk/exclusive-average-speed-cameras-cut-welsh-air-pollution-by-half/