This post is a guest blog by local journalist Carlton Reid, the executive editor of Bike Biz. Carlton lives in Jesmond and, as his parents live in Fawdon, he regularly rides his bike on Gosforth High Street.

Cycle route, John Dobson Street, Newcastle upon Tyne

The wide, smooth and kerb-delineated cycleway on John Dobson Street is believed by many to be the first and finest such infrastructure in the North East for people on bikes. It’s the finest (oh, for such width, buttery asphalt and protection in Gosforth!) but it’s not the first. Hold on to your cloth-caps because – to the surprise of most people – the North East was once a leader in providing for cyclists.

For one, there was the Tyne Pedestrian and Cyclist Tunnel, a wonderful piece of protected infrastructure, and which is currently being refurbished (although it’s taking a wee while). This two-tunnel tube was opened in 1951, sixteen years before the Tyne Tunnel for motor vehicles. At its peak, 20,000 users – mainly shipyard workers – rode or walked through the tunnel each day.

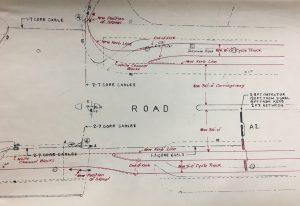

And the North East had an even earlier claim to cycling fame: it had the sort of wide, protected cycleways that we today associate mainly with the Netherlands. There were “cycle tracks” on each side of major roads, such as the A167 (or former A1) at Neville’s Cross, and on Durham Road in Sunderland.

These roads were built in the 1930s – the Ministry of Transport would only provide fat grants for them if the local authorities included wide cycleways, too. Britain once had 280 miles of these Dutch-inspired cycleways and I’ve launched a Kickstarter campaign to research and then rescue many of them.

Well, I’ll be doing the research bit, the rescue bit will be handled by fellow Geordie John Dales, who, despite being based in London, is currently helping Newcastle City Council with the Blue House Roundabout Working Group, the proposals for Gosforth High Street and the Streets for People project.

As John says in the project video below this historical Kickstarter is highly relevant today because the space for cycling that many planners and politicians say isn’t there is there!

Many of the North East cycleways I’ll be helping to resurrect are hidden-in-plain-sight – they’re clearly and obviously there but they’ve been there so long nobody knows they were built for cyclists. Others around the country are buried, and lie a few inches beneath verges that people assume are just wide expanses of roadside grass.

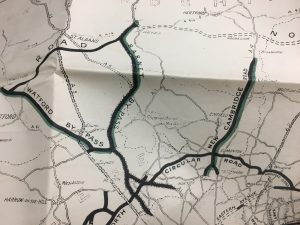

The majority of the 80 innovative-for-the-time cycleways – installed between 1934 and 1940 – are on the outskirts of London, but the next hotspot, as you can see from the map below, is the North East. There are 1930s cycleways north of Seaton Sluice and on the Links at Whitley Bay, and there’s a sliver beside junction 63 of the A1 at Chester-le-Street (blink and you’ll miss it, the rest of the cycleway has long since been grubbed up). And Team Valley – built between 1936–39 – was originally equipped with cycleways on each side of Kingsway.

In contrast, the whole of Scotland has three schemes, and Wales just one.

Ministry of Transport London map of 1937 showing proposed cycle routes – image courtesy of Carlton Reid

That there were 280-miles of Dutch-style pre-World War II cycleways in the UK came as a complete surprise to me. I started researching them for the 1930s chapter in my new book, Bike Boom, due out in May from Island Press of the US. I knew there were a few of these “cycle tracks” in the UK – the one on Western Avenue in London, and which was the first – is relatively well known, but then I kept finding more and more.

Researching ministerial papers in the National Archives I even discovered that the Ministry of Transport was provided with engineering drawings and support by its equivalent in the Netherlands. “Go Dutch” as a cycling clarion call isn’t a modern thing at all!

In the project video John says: “One of the things that’s quite legitimately raised about British traffic engineers and highway engineers is that ‘we don’t know how to do this stuff’ or ‘we’ve never done it … we have to look abroad.’ What’s fascinating about these is the fact that – piecemeal as they were – we have done it.”

He adds: “Trying to recover these tracks, these paths, hidden in plain sight, is a really terrific opportunity. Who knows how many of the 280 miles are genuinely in a position to be brought back in? But let’s say it’s just a hundred, which is highly likely, that’s a hundred we haven’t got at the moment in effect, but also a hundred that could become a 150 or 200 really quickly by joining them up to other stuff that’s going on.”

John Dobson Street, Newcastle upon Tyne

The short John Dobson Street cycleway cost £1.7m to build. It’ll cost significantly less than that to restore some of Britain’s first cycleways and, if they can be meshed into modern cycleway networks, and given the sort of design treatments that we know work – such as protection at junctions – then, finally, these 1930s cycleways will be used again.

Of course, before we can go cap-in-hand to the Department of Transport and local authorities we have to do the initial legwork and that will involve succeeding on Kickstarter.

1930s cycle sign courtesy of Carlton Reid

After just a day we’ve raised £4,500 of our £7,000 target so demand is clearly strong. Those who back the project get exclusive behind-the-scenes access to our work. You’ll be more than welcome to join us as we aim to revive and protect for future generations what was once an ambitious – albeit disjointed – network of cycleways.

With today’s impetus for active, clean and healthy travel there’s a greater-than-ever desire for these sort of protected cycleways.

This photograph of the former A1 at Neville’s Cross is courtesy of the Durham County Archive).